The apparatus is made of heavy cut crystal, by Sautier, of Paris, at a cost of upwards of $10,000, including additions by Chance, of Birmingham, and is illuminated by one of Doty’s concentric 4-wick lamps, and has been pronounced, by persons who have seen it at a long distance, to be a most brilliant light, looking like a large ball of fire. At night it will be more useful still, as from the mast of a vessel at sea it will be seen a long distance off, probably 25 miles. It will be very useful as a day beacon for ships at a distance, and will enable persons to distinguish the island long before they can see it or come near its dangerous bars. The tower is an octagonal wooden building 86 feet high, painted alternately white and dark brown, and stands about 13 miles from the end of the Island. The light is a powerful fixed white dioptric, second order, and is elevated 120 feet above high water, and in clear weather can be seen at a distance of 18 miles, although it has been reported to have been seen much farther off. The Department of Marine noted the completion of a lighthouse a steam fog whistle on both the east and west ends of Sable Island in its 1873 report:Ī new lighthouse has recently been erected on the east end of Sable Island, near Lighthouse Hill, so-called, and the light was first exhibited on the 14th February last. In 1870, parliament voted an initial $5,000 for the purpose of constructing navigational aids on Sable Island. Others felt a light would help mariners deduce their true position and avoid the treacherous hazards. Those who opposed a lighthouse felt that its presence would entice mariners to run for the lighthouse and lure them closer to the deadly shoals and sandbars surrounding the island. Placing a lighthouse on the island might seem an obvious way to prevent shipwrecks, but this topic was fiercely debated. That year, merchants and others concerned in navigation petitioned for the establishment of a lighthouse on the “dreaded island.” No lives were lost in three of the wrecks, but the entire crew of the American brig Abigail perished when it ran aground in October. In 1835, Joseph Darby, superintendent of the island, noted that four vessels had been lost on the island that year. Four outposts distributed around the island were each staffed by a keeper and an assistant, who regularly patrolled the shores looking for any signs of trouble. Potatoes and other root crops, like turnips, carrots, and beets, were also raised for food. Cattle were brought to the island’s fly-free environs and pastured on the grass along with a few sheep and pigs to provide fresh meat. To offset the cost of maintaining the lifesaving operation, some of the island’s herd of wild, hardy horses were regularly taken ashore and sold, and the islands residents picked wild cranberries that were likewise sold on the mainland. Photograph courtesy Library and Archives Canada

This humane establishment was staffed until 1958.Ī newly constructed dwelling at East End in 1935 The superintendent was initially paid a salary along with a percentage from the net proceeds of wrecked property that his team saved. The station was typically staffed by a superintendent with around fifteen men under his command.

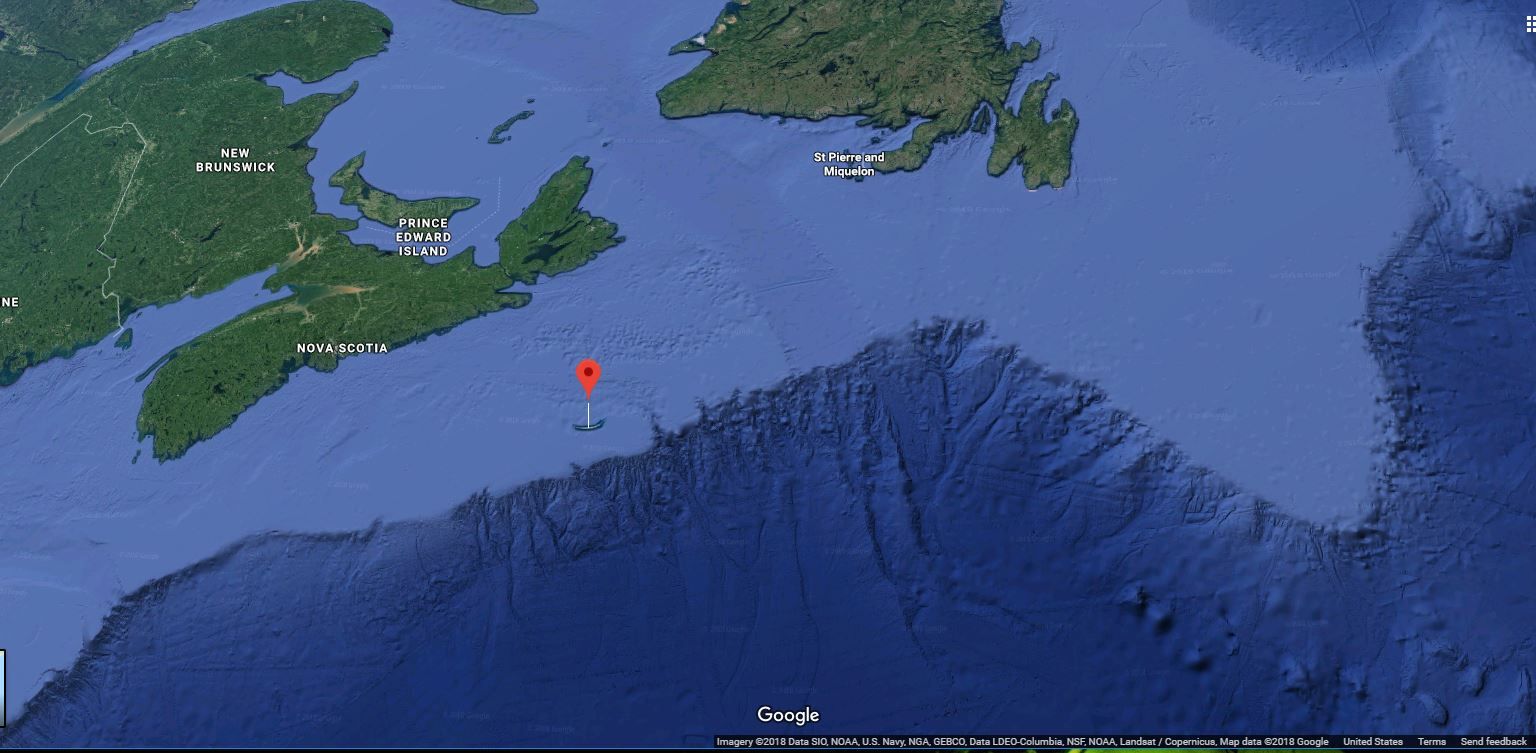

The island’s ever shifting sandbars have snagged an estimated 350 vessels over the years.Ĭoncern for the fate of shipwrecked victims stranded on Sable Island led to a lifesaving station being built in 1801. The island’s low profile and location near a major transatlantic shipping route, coupled with thick fogs, treacherous currents, and sandbars that extend a great distance from the north and south tip of the forty-three-kilometre-long island, have led to numerous shipwrecks. Sable Island, literally “Sand Island,” is a crescent-shaped ribbon of sand situated 175 kilometres southeast of the nearest point of mainland Nova Scotia.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)